Written By Nao Sims at Honey Grove Farm, member of The Comox Valley Beeclub

originally posted July 11, 2013

There is nothing I like better than high-summer in the bee-yard. The hum of the hive on a sunny day is one of the most beautiful songs I have ever heard.

The smell of warm wax and honey that rises up off the hives and permeates the lower field where they sit, is utterly transporting.

Yes, at long last the sun has come out on the Pacific West Coast of Canada, and our second nectar flow has finally begun.

The bees are busy from dawn to dusk and the whir around the bee-yard brings a deep down contentment to my whole being.

Here on Honey Grove Farm, located in rural Comox Valley BC, on Vancouver Island, we had a great deal of rain during the months of May and June. The rain combined with a dearth toward the end of May could have brought a number our hives to starvation, had we not intervened and fed them sugar syrup. Despite the abundant honey stores that the bees came through winter with, they still did not have enough. Although we are dedicated to planting more bee-food here on our property, we have not yet managed to have enough flowering at the time when our bees seem to need it most.

And so, our dedication to create a sanctuary for honeybees continues, as we endeavor to plant more flowers and trees to support our bees. It is common knowledge that a great number of beekeepers will move their bees to the nectar-flow, as opposed to bringing the nectar-flow to their bees. Here on Honey Grove, however, we are interested in the latter (that is bringing flowers to bees, as opposed to bees to flowers). The below image is of a bee on phacilia, a flower which bees love that is rich in nectar as well as pollen, and that we have planted in abundance on our farm.

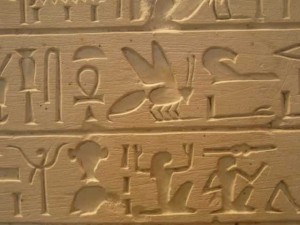

In our culture, in these modern times, beekeepers move their bees for pollination reasons as well as honey production. In fact, up until the early part of the 20th century, it was believed that this is a fairly recent practice (recent being over the last two to three hundred years) however, in 1914, at an archeological dig in Egypt, a number of papyri were uncovered which once belonged to Zenon, a Greek official who lived at Philadelphia in the Fayum, about the middle of the third century before Christ.

From the information recorded on these papyrus it would seem that ancient Egyptians also practiced what the Germans call Wanderdienenzucht, that is, moving beehives to different districts in order to take advantage of the earlier and later flowering plants. One of these documents reads:

“To Zenon greeting from the Beekeepers of Arsinoite nome. But it is now 18 days that the hives have been kept in the fields, and it is time to bring them home and we have no donkeys to carry them back. Unless donkeys are sent at once, the result will be that the hives will be ruined and the impost lost. (C.C. Edgar, “Selected Papyri from the Arrchives of enon,” No.106, p.41, in Annales du Service des Antiquities de l’Egpte, vol xxiv.)

I must admit that the first time I read this, I was in some disbelief, for I was always under the impression that moving hives was a more modern beekeeping practice, and yet the above quote suggests that beekeepers have been moving their hives for thousands of years, imagine. However, I think it is important to note that moving hives on carts pulled by donkeys, a few miles from one field to another, is a very different thing than moving hives on 18 wheeler trucks, thousands of miles, back and forth across America to pollinate mono-crops of almonds and blueberries.

All of this leads me to appreciate that being a beekeeper in these modern times is a very different practice than it once was. Here on Honey Grove, we are not fans of moving our bees great distances to pollinate mono-crops or for honey production. Sometimes we will take our bees on a 20 minute journey up the mountain into the alpine, to collect the clean unpolluted nectar of fire-weed that grows there, but that is all.

It is now recognized by scientists the world over, that moving bees to pollinate mono-crops is not the best thing for our beloved bees. Bees need a variety of nutrients to be fully nourished, healthy and thriving, and this means taking the nectar and pollen from a variety of flowering plants. Undernourished or malnourished bees appear to be more susceptible to pathogens, parasites and other stressors. Beyond this, a great majority of farmers are still using chemicals on their crops, and bees pollinating those crops are exposed to a plethora of toxins, some of which have the potential to not only weaken the bees, but to kill them outright. It has also been shown that leaving bees inside a hive with blocked entrances for 8 -24 hours during transport, is very stressful for bees, as they cannot leave to defecate and there is often not enough ventilation.

All of this considered, I have decided not to move my bees anywhere, and instead, to bring the flowers to my bees. It is my belief that bees have served humanity for far too long now. It is now time for us to be of service to our bees, in whatever ways we can. This does not mean we need to keep bees ourselves even. You do not need to be a beekeeper to plant flowers that support bees, or to buy honey from your local organic beekeeper, supporting practices that benefit bees.

For me, as a beekeeper, keeping bees means serving bees, it means creating an environment that fully supports my bees throughout the year. It means practicing organic methods of beekeeping in whatever ways I can, and not treating my bees with antibiotics for disease prevention. It means remaining dedicated to holistic methods of hive management which includes Integrated Pest Management ( doing a number of non-invasive practices throughout the beekeeping year to reduce the stress levels in the hive and to keep mite counts down). At this time in history, we can no longer ask what the bees can do for us, but rather, we must ask ourselves, what we can do for them.

Flowers we can all plant for bees

March/ April

Crab apple

Malus sylvestris

Bluebell

Hyacinthoides non-scripta

Cytisus scoparius

Cherry

Prunus avium

Bugle

Ajuga reptans

Heather

Erica spp.

Flowering currant

Ribes sanguineum

Lungwort

Pulmonaria officinalis

Pear

Pyrus communis

Goat willow

Salix caprea

Red dead nettle

Lamium purpureum

Rosemary

Rosmarinus officinalis

White dead nettle

Lamium album

May/June

Bird’s-foot trefoil / Paul

Marten

Birds foot trefoil

Lotus corniculatus

Chives

Allium schoenoprasum

Comfrey

Symphytum officinalis

Foxglove

Digitalis purpurea

Honeysuckle

Lonicera periclymenum

Kidney vetch

Anthyllis vulneraria

Lupin

Lupinus spp.

White clover

Trifolium repens

Poppies

Papaver spp.

Phacilia

Raspberries

Rubus idaeus

Red campion

Silene dioica

Sage

Salvia officinalis

Thyme

Thymus praecox

Tufted vetch

Vicia cracca

Meadow cranesbill

Geranium pratense

Wisteria

Wisteria sinensis

July/ August

Borage

Borago officinalis

Bramble

Rubus fruticosus agg.

Buddleia

Buddleia davidii

Cornflower

Centaurea cyanus

Hollyhock

Alcea rosea

Common knapweed

Centaurea nigra

Lavender

Lavandula spp.

Lesser burdock

Arctium minus

Wild marjoram

Origanum vulgare

Mint

Mentha spp.

Purple loosestrife

Lythrum salicaria

Red clover

Trifolium pratense

Scabious

Scabiosa columbaria

Sea holly

Eryngium maritimum

Snap dragons

Antirrhinum majus

Sunflower

Helianthus spp.

Teasel

Dipsacus pilosus

Thistles

Cirsium dissectum

Vipers bugloss

Echium vulgare